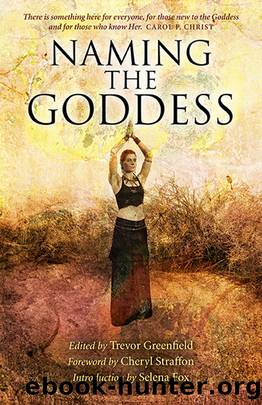

Naming the Goddess by Trevor Greenfield

Author:Trevor Greenfield [Greenfield, Trevor]

Language: eng

Format: epub, pdf

ISBN: 978-1-78279-475-2

Publisher: John Hunt Publishing

Published: 2014-09-26T00:00:00+00:00

Eostre

Little is known from historical records about the Anglo-Saxon Goddess Eostre. Her name comes down to us in the English title for the Christian holy day of Easter as well as the German name for the same day, Ostern. The name Eostre ultimately derives from an Indo-European root that refers to sunrise, the direction of east and the concept of shining; we can see a cognate in the name of the Greek Goddess of dawn Eos.

The most accessible source of historical information about Eostre is a medieval treatise called De temporum ratione (The Reckoning of Time), all about calendars and related methods of measuring time penned by the 8th century English monk Bede. In this work he explains that during the month named after Eostre, ÄosturmÅnaþ (presumably corresponding to April since he lists it as the fourth month of the year), the Pagan Anglo-Saxons used to hold feasts in her honor. He also states that the practice had died out by his lifetime. In addition to this written reference, a fair amount of archaeological evidence exists to show devotion to Eostre across much of pre-Christian Britain and Germany. Dr. Phillip A. Shaw of the University of Leicester details this evidence in his book Pagan Goddesses in the Early Germanic World: Eostre, Hreda and the Cult of Matrons (Studies in Early Medieval History Series, Duckworth Publishers, 2011). His examination of more than 150 votive inscriptions from the second century BCE, all found in the region of the Rhine River, shows that Eostre had an extensive following in Germany before the introduction of Christianity. Dr. Shaw also points to a number of place names in England as well as personal names in Germanic-speaking areas that derive from Eostre, suggesting that she was an integral part of the early culture of those regions.

Our largest source of folkloric information about Eostre comes from the 19th century German folklorist Jacob Grimm. He collected oral folk traditions from throughout Germany and compiled them into a written collection titled Deutsche Mythologie, usually translated as Teutonic Mythology. Based on the German term for the month of April (âostermonat,â earlier âôstarmânothâ) and the Old High German word for Easter (Ãstarâ), Grimm reconstructed the German form of the Goddessâ name as Ostara. He connected her with the concepts of dawn and light through both the root meanings of her name and the time of year with which she is associated. Rightly or wrongly, he also connected many Germanic Easter traditions â bonfires, sunrise dances, drawing holy or blessed water on Easter morning, Easter eggs and the Easter feast â with Ostara and pre-Christian practices.

The hunting of hares, called âhare coursing,â was a popular springtime or Eastertide sport in Britain for a number of centuries. It finally died out in the 20th century, but was long considered to be related to pre-Christian springtime practices involving Eostre. This connection may have little basis in fact but it developed a strong underpinning in folklore, possibly due to the influence of such works as Frazerâs Golden Bough, and gives Eostre a firm association with the hare in popular culture.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Predicting Your Future through Astrology by Sita Ram Singh(510)

The Practice of Classical Palmistry by Madame la Roux(431)

How to Be Your Own Therapist by Owen O'Kane(422)

Magic of Isis: A Powerful Book of Incantations and Prayers by Alana Fairchild(373)

2021 Quantum Human Design Evolution Guide by Karen Curry Parker(330)

Yoga for Beginners: Your Natural Way to Strengthen Your Body, Calming Your Mind and Be in The Moment (Yoga Poses) (A Better You Book 1) by Susan Mori(316)

Writing Guide for Memorandum of Understanding by unknow(306)

Christmas Witch (Hot Hex 3) by Susan Stephens(285)

Tarot de Marseille by Marius Høgnesen & Paul Marteau(273)

Africa's Diabolical Entrapment: Exploring the Negative Impact of Christianity, Superstition and Witchcraft on Psychological, Structural and Scientific Growth in Black Africa! by Larr Frisky(273)

Learn Cold Reading: The real secret of mind readers by Reynolds Ethan(271)

Shadow Worlds by Andrew Wood(269)

Design Guide to Learn Calligraphy: Fonts, Styles, Pens, Letters, & Numbers by Agatha Adams(261)

The Stuff of Dreams by Edward Lucas White(261)

The Enfield Poltergeist Tapes: One of the most disturbing cases in history. What really happened? by Melvyn J. Willin(259)

The Watkins Tarot Handbook by Naomi Ozaniek(257)

Miracle Minded Manager by John Murphy(245)

The World's Most Mysterious Objects by Patricia Fanthorpe & Patricia Fanthorpe(237)

Witch: A Magickal Journey by Fiona Horne(233)